Kingdom of Rhode Island

Maps are symbols of progress, imaginations of political communities, and sources

of scientific

truth. They are also tools of empire: alive with ambition, but also silent, stifling creatures

that erase the histories of peoples who originally oversaw and cultivated the land which they

chart.

Kingdom of Rhode Island is a product of a semester-long grapple with those

complicated

dichotomies.

When: Dec, 2020

Class: Development’s Visual Imaginaries: Still and Moving Images That Shaped the Field

A series of artwork and contexualizing essay challenging viewers to perceive maps

as

indexical, selective, and colonialist.

![]()

![]()

Maps are symbols of progress, imaginations of political communities, and sources

of scientific

truth.

They are also tools of empire: alive with ambition, but also silent, stifling creatures that erase the

histories of peoples who originally oversaw and cultivated the land which they chart.

Kingdom of Rhode Island is a product of a semester-long grapple with those complicated dichotomies.

I was unsure of how I wanted to position myself in this discussion: as an observer, commentator, a

change maker, or perhaps, all of the above? When integrating my own subjective experiences into visual

imaginaries that have great significance in the shaping of territories and its peoples, do I run the

risk of simplifying and trivializing a complicated history that I cannot even claim? Furthermore, what

is the purpose of creating an artwork like this outside the task of demonstrating my learning this

semester? Is it solely to help myself ‘locate, perceive, identify and label’ my own grappling with these

issues, or can it contribute to a public narrative that can help 'guide writing of legislation,

formation of policy, and design of practices?’

With these questions in mind and ideas of many different ways I wanted to piece all of it together, I

began by simply studying hundreds of maps and drawing inspiration from that process. Maps have a

spatiality fundamental to all cultures, but I wanted to ground my exploration within the boundaries of

New England for the main reason that this is a land I have developed a personal relationship with in the

past three years of studying here. This is a land that I felt like I was a part of —— the specific

borders, localities, waterways I was looking at on parchment existed in a space that was not only

intellectual but also experiential. The sandy Newport beaches, windy India Point Park overlooking the

expansive Narragansett bay were not solely metaphorical, but had experience-connectivity. In fact, I

remember feeling a strange delight when I found a fine-print engraving of “Sheldon St” in Providence’s

first city plan dating back to the 1700s. There was a weird joy to knowing that the street I live on

existed in the minds of people centuries before I had moved there. Just those two simple ink lines

running parallel to the water allowed me to imagine how the land had changed over the years; I could

locate myself in Providence’s history. This land is also one whose history I wanted an excuse to better

understand. Sifting through topological engravings from the late 1500s onwards, I was fascinated by the

elegant calligraphy, the ornate ships battling invisible winds used to define regions of water, the

detailed etchings of royalty and indigenous peoples on map edges used to stimulate the viewers’

imagination of the boundless possibilities barely curtailed within the parchment’s four borders.

In my photography, I have been increasingly fascinated with creating semi-altered new realities through

collage, inspired by work like those by Edward Steichen and Noriko Furunishi.

![]()

I wanted to experiment with a similar kind of prismatic effect in this piece, on

both an

aesthetic and conceptual level. I started by downloading around three dozen maps of the Rhode Island and

New England area, including anything from ethnographic maps of indigenous territories, treaties, and

languages, to modern day google maps of the Providence area. I mapped them out in the same document,

playing around with opacity, softened edges, order of appearance, placement, and maskings. These

individual etchings and pieces of century-old parchment mapped out the same land, yet had such vastly

different audiences, purposes, and sources of power. For example, some are powerful because of their

specificity and claims to non-indexicality, which “enable forms of association that make possible the

building of empires” (Turnbull, 1989). Others map out modern day indigenous nations, but have no intent

to represent official or legal boundaries. Rather, they aspire to “better represent how Indigenous

people want to see themselves” (Native Land, 2020). Despite drawing on the same points of reference,

they are still physically vastly different: save for placements of large urban centers and coastal

lines, almost none of the boundaries overlap completely; in fact, overlaying them on top of each other

and scaling them proportionally, boundaries began to take on a kaleidoscopic, hallucinogenic form: land

masses became blotches, roads and populous areas became spheres of influence.

Did I want all of them to merge together, to render the boundaries porous and permeable as if they were

created by the same cartographer? Should I highlight the different layers of parchment and each of their

borders, emphasizing the many framings that can define the same land? When is something a map versus a

picture? What are the implications of transforming a map into a work of art? Does it retain its sources

of power as a universal and scientific arbiter of truth, a tool for empire, or a means to strengthen the

spiritual bonds that people have with the land, its history and its meaning? Or does it trivialize, poke

fun, and demean?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The map as a metaphor holds an especially persuasive and pervasive place in my

own imagination.

When I first began reading fantasy fiction, I remember being completely enraptured by the

colonial-styled diagrams in the beginning of each book that mapped out mystical castles, magical

forests, and dangerous grasslands. Even while I was reading through, I always had a thumb on that page;

any time a new city had been besieged by an evil king, I would quickly flip back to the map to ground my

imagination. The black-ink-ed shrubbery would come to life, and blue-scaled dragons bearing brilliantly

armed sorcerers would jump from their midst. Later, when I created my own worlds, in the bedtime stories

for my brother or in the games of play-pretend as we galloped around in the garden, one of the first

things I did was to soak a piece of paper in coffee to create semblance of an ancient artifact recently

discovered. Within those stained folds, I would create my fantastical landscape in which I would hide my

treasures. When I ‘grew too old’ for that, I transitioned to creating maps of my surroundings, finding

great solace in detailing the streets four or five blocks out around my Shanghai apartment. It gave me a

sense of ownership and identity that I did not know I sought.

I elaborate so extensively on how integral the map has been in fueling my own visual imaginary not

because I believe my experience is unique; if anything, it is because it is so shared. According to the

Swiss educational psychologist Jean Piaget, spatiality is fundamental to our consciousness and our

understanding of experience (J. Piaget & B. Inhelder, 1967). It is also because it allows me to situate

you, the viewer, in a similar context and framing when viewing these selected visual imaginaries

integral to development. This project has compelled me to look back at my childhood penchant for maps

and better understand them, but also realize the parallels that exist within the

imaginer-colonizer-explorer mindset. Through channeling and critiquing the impulses that shaped the

formation of colonialist maps, The Kingdom of Rhode Island seeks to answer some of the questions posed

above by presenting a counter narrative to the historical and modern day mappings that have shaped our

relationship with the land.

I remember finding solace in the universality of my maps: showing one to someone was like inviting them

into my world, as the inked boundaries gave it a non-indexicality that simply describing it lacked. It

elevated my imagination to the realm of knowledge. Yet, maps are inherently indexical, and it is

dangerous to think they are not. To think they are immutable requires the belief that the land on which

you can imprint your universal imaginary is a blank slate. Anything that interferes with this

imagination, anything that existed before, has to be eradicated in an ultimately violent process.

Patrick Wolfe, an academic at the University of Melbourne explains the political ramifications in his

interview with J. Kēhaulani Kauanui:

If you’re a settler, you’ve come with a social contract, you’ve done all these European things

involving

subjecting yourself to the rule of the sovereign; the natives never did that. Their rule of law was

prior to colonial rule, and the colonizer’s legal system simply can’t deal with that. It can’t deal

with

something that originated outside of itself. So, even on a political level, quite apart from the

economic competition, all traces of Native alternatives need to be suppressed or contained or in

some

way eliminated. (Kauanui, J., 2012)

Maps frame ideas and peoples as mutually exclusive bodies with impermeable boundaries, when really, they

are overlapping, porous spheres, layered atop of each other, fading into each other, transgressing upon

each other. They create the idea that boundaries are natural rather than socially created; they justify

the borders necessary for a nation's political imagination. They simplify the trauma and displacement

inherent to the colonial enterprise that led to their creation, in the same callous and apathetic way

territory transactions like the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 do so with complete disregard for

how waterways, lands and the people living on territories know no artificial boundaries designated by

war.

Maps are also selective in the narratives they tell and the ones they choose to obliterate. In the 9

panels of Part II, different layer orders and opacities bring to prominence different borders,

landmarks, and focal points. The inclusion of maps demarcating the same region over 3 centuries also

shows a map's two dimensionality when it exists alone; they are a product of history, but silence the

history of the land. Tracking them across time, we see they can also be markers of progress: only four

centuries ago, "maps of New England consisted of a single line separating ocean from land… the interior

remained blank" (Cronon, 2003). The power of the 'Western' mapping enterprise is its ability to be

"mobilized to cover the whole earth, if not the universe," whereas indigenous ones are usually linked to

the body of knowledge that constitutes culture and retain a distinct locality (Turnbull, 1989). With the

term "enterprise," I also wish to pinpoint the sense of arrogance that comes with such desire to chart

the whole world: to believe that the world is yours to be mapped, that you have the right to draw your

heavy-handed mystical castle walls and name grasslands after yourself, is vividly imaginative when you

are a child but violently imperious when you are an army of thousands ready to eliminate whatever that

stands in the way of this imagination.

This brings me to my final point, which is that maps carry an inherently settler-colonialist lens that

sees land as territory. Item 23 of the Homestead Act of 1862, which promoted the settlement and

development of the American West by granting 160 acres of ‘public’ land to anyone who paid a small fee,

enumerates that “land is one of the first institutions of the state.” This captures well the

relationship between land, state power and its subjugation of the people who live on the land. The

inclusion of 'Native Land' in Kingdom of Rhode Island, which maps groups of indigenous people as

holographic, colorful, and permeable shapes, attempts to draw focus to how land inherently comes with

ways of life, culture, and earned, spiritual and intimate knowledge of the landscape. It offers the

indigenous relationship with land as a counter narrative, seeing land as more than the resources it

offers, the key to economics and a means of production. According to Cronon, “Many European visitors

were struck by what seemed to them the poverty of Indians who lived in the midst of a landscape endowed

so astonishingly with abundance” (Cronon, 2003). The Europeans practiced land ownership, while Indians

believed in territorial rights; the Europeans lived off the land, while Indians were caretakers.

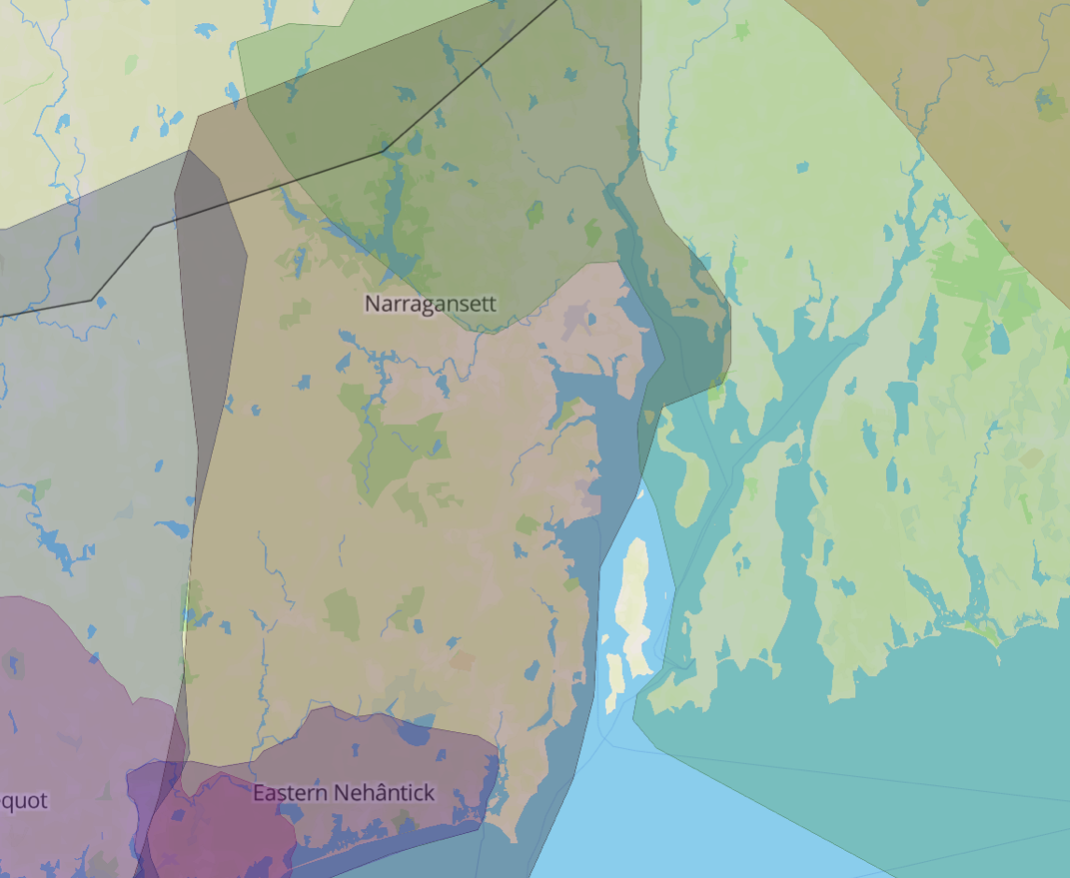

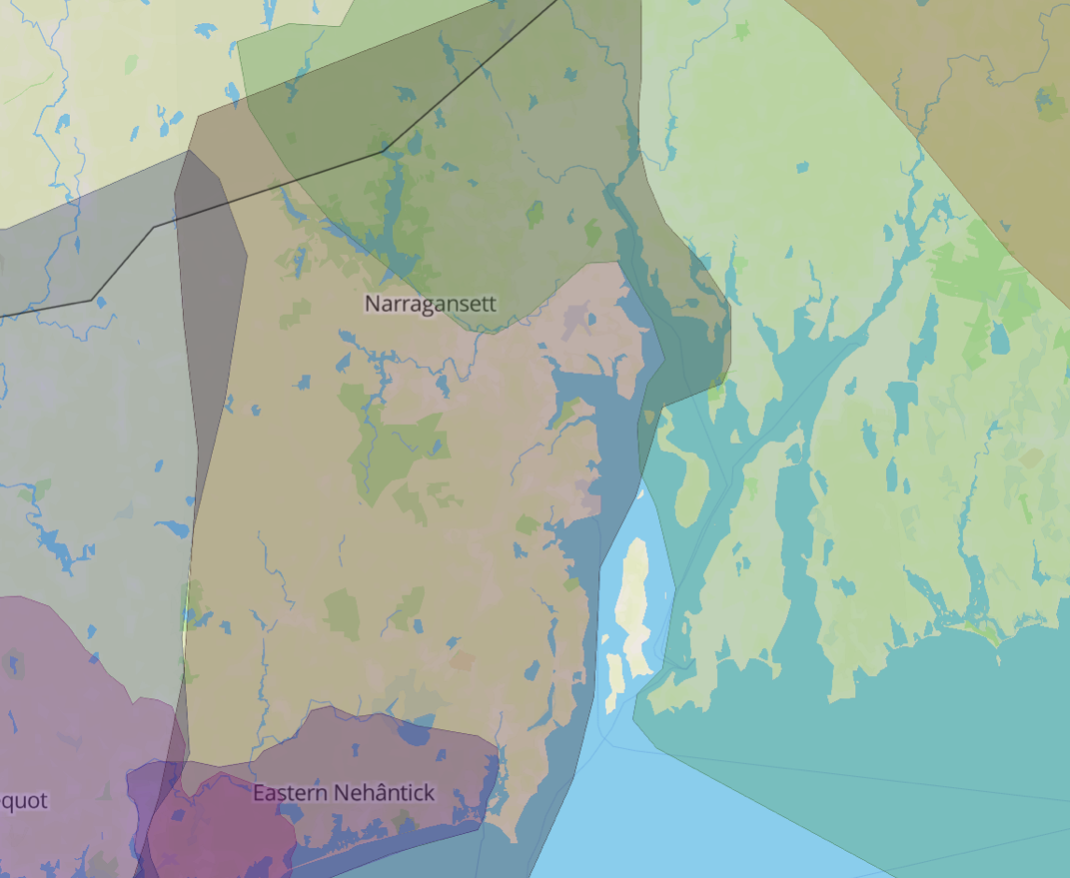

Above: zoomed in view of 'Native Land', a digital map that strives to "map Indigenous

territories,

treaties, and languages across the world in a way that goes beyond colonial ways of thinking" that

is included in the final piece

Ultimately, Kingdom of Rhode Island challenges viewers to perceive maps as indexical, selective, and

colonialist. I want to end by acknowledging the limitations to this counter narrative. First is in the

data collection and the maps themselves: as a student at a university founded upon the Western

tradition, almost all of the maps that I found in library archives were created by European settlers.

Thinking about maps as bodies belonging on paper with absolute co-ordinate systems neglects the

indigenous treatment of maps as objects that "serve specific functions in particular contexts" (M.

Lewis, 'Indian delimitations of primary biogeographic regions', 1987). Examples include Stickcharts from

the Marshall Islands and carved wooden coastal charts carried in their kayaks by Greenland Inuit

(Eskimo). Secondly, I may not be an American settler, and I may not have voluntarily displaced anyone or

massacred any peoples in my journey to study abroad in a foreign land, but I am a beneficiary of this

system that continues to dispossess and eliminate indigenous people. The privilege of approaching topics

of territory from an intellectual and artistic viewpoint cannot be overlooked, especially as I draw upon

knowledge and belief systems of cultures not belonging to my own.

Finally, I'd like to thank Professor Geri Augusto and Ms. Heather Cole for pointing me towards many of

these resources that started me on this journey.

Comments from Professor Augusto

Dec 20 at 4:36pm

Excellent, highly inventive work; it needs to be part of an

exhibition! Given the

respect with which you approach this entire work, I do not think that indigenous people would see it as

exploitative of you to treat the themes in your essay, and render your ideas in the way that you did.

The essay attests to a great deal of careful research and thought about mapping, and the ideational,

political and social work that maps do, particularly as tools of empire. Your reimagination of the

Kingdom of Rhode Island in maps discloses how these constructions further manifest and inscribe empire

on the land as well as on subjugated peoples--all while also being aesthetically pleasing to the viewers

(or some of them.) I note with satisfaction the self-reflexive, nuanced and highly-detailed discussion

of your process, including the interrogation of how, or whether, your knowledge and art-creative work

might help instigate alternative public narratives. Bringing in the "prismatic effect" of work by

Steichen and Furunishi--work I did not know about, so thank you-- was helpful, as well, in bringing out

your aims and aesthetical choices. (India Point Park, by the way, has been one of the sources for my own

photo-essays, so that adoption of another's land, of which you write, resonated with me, too.) This work

elucidates frames and categories, boundaries and power, and of course, the blurred line where

imagination and physical beings and entities emerge on a two-dimensional field, even in the most

"scientific" of maps. I am glad to see such good use made of the references I suggested; you put

together a very good, interdisciplinary bibliography. Certainly this final project creates a most

persuasive and art-historical counter-narrative about settler colonialism, and settler epistemologies.

Hence it does belong within the study of development's emergence as ideas and practice right here in the

USA. Things got their start in New England, after all.

References

Act of May 20, 1862 (Homestead Act), Public Law 37-64, 05/20/1862; Record Group

11; General Records of the United States Government; National Archives.

Cronon, W. (2003). Changes in the Land. New York: Hill and Wang.

Kauanui, J. (2012). Settler Colonialism Then and Now: A conversation between J. Kēhaulani Kauanui and

Patrick Wolfe. Politica & Società. Retrieved from

https://nycstandswithstandingrock.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/kauanui-wolfe-2012.pdf

Lewis, G. Malcolm. (1987). "Indian Delimitations of Primary Biogeographic Regions." In A Cultural

Geography of North American Indians, edited by Thomas E. Ross and Tyrel G. Moore. Boulder CO: Westview

Press.

Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1967). The child's conception of space. New York: W.W. Norton.

Turnbull, D., & Watson, H. (1989). Maps are territories: Science is in atlas: A portafolio of

exhibits.

Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Maps that I use within the piece:

Foster, J. (1677). A Map of New-England, Being the First That Ever Was Here Cut, and Done

by the Best Pattern That Could Be Had, Which Being in Some Places Defective, It Made the Other Less

Exact: Yet Doth It Sufficiently Shew the Scituation of the Country, and Conveniently [Map]. In Newberry

Library. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://archive.org/details/nby_456090.

Google Maps (2020). Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://maps.google.com/

Green, J. (29.1). A map of the most inhabited part of New England: containing the provinces of

Massachusets Bay and New Hampshire, with the colonies of Konectikut and Rhode Island, divided into

counties and townships: . [London]: Thos. Jefferys, geographer to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales

near Charing Cross.

Harris, C. (1795). A map of the State of Rhode Island taken mostly from surveys [Map]. In JCB Map

Collection. Providence, RI: Carter & Wilkinson. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from

https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/s/40oa18.

Lewis, Samuel, "A map of part of Rhode Island: showing the positions of the American and British armies

at the siege of Newport, and the subsequent action on the 29th of August 1778 " (1807). Brown

Olio. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University

Library. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:41284/

Manuscript map of Little Compton, Rhode Island, ca. 1681. (1681). In JCB Map Collection.

https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/s/gp04r4. Little Compton, RI.

NativeLand.ca. (2020). Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://native-land.ca/

Reid, J. (1796). The state of Rhode Island, from the latest surveys B. Tanner, delt. & sculpt. [Map]. In

JCB Map Collection. New York: American Atlas. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from

https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/s/2ivpj1.

Rider, S. S. (1903). The Lands of Rhode Island as Canonicus and Miantonomo Knew Them [Map]. Office of

the Librarian of Congress at Washington. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from

https://rifootprints.com/2012/06/04/354/

Witherell, Eugene E., "A map of the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 1636-1740"

(1925). Brown Olio. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University

Library. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:41837/

A Topographical Chart of the Bay of Narragansett in the Province of New England... [Map]. (1777). In JCB

Map Collection. London: Engraved & Printed for Wm. Faden, Charing Cross. Retrieved December 14, 2020,

from https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/s/q01s34.